| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

{{main|History of Kosovo}} |

{{main|History of Kosovo}} |

||

=== |

===Ancient and medieval periods=== |

||

Kosovo was known in antiquity and up to the 19th century as [[Dardania]]<ref>[http://www.albanianhistory.net/texts/AH1883.html Arthur Evans, “Some Observations on the Present State of Dardania,” R. Elsie ed., ''Albanian History'']</ref> (from Albanian word ''dardhë'' = pear; literally ''Pearland'') after the Illyrian tribe [[Dardani]].<ref>Noel Malcolm, ''Kosovo: A Short History'' (UP: New York, 2003) 31.</ref><ref>Aleksandar Stipcevic, ''Iliri'', 30; Mirdita, ''Studime dardane'', 7-46; Papazoglu, ''Central Balkan Tribes'', 210-69 & "Dardanska onomastika"; Katicic, ''Ancient Languages'', 179-81</ref> Historical sources mention a Kingdom of Dardania as early as 4th century B.C., which included Kosovo and parts of surrounding areas.<ref>Bep Jubani, "Mbretëria Dardane," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 26-29.</ref> Prominent kings include [[Longarus]], Monunius, and Bato, who engaged in frequent wars against [[Macedon]] and achieved numerous successful victories.<ref>Bep Jubani, "Mbretëria Dardane," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 26-29.</ref> There is also an account of wars with the Celts. Dardania was well-known for its gold resources and ancient writings describe the Dardani as fine producers of jewels. Major cities included Damastion, Naissus ([[Nis]], [[Serbia]]), Scupi ([[Skopje]], [[Republic of Macedonia|Macedonia]]), and Ulpiana.<ref>[http://www.shqiperia.com/kat/m/shfaqart/aid/71.html Historia e Shqipërisë, “Mbretëria e Dardanisë: Territori dhe popullsia,” ''Shqiperia.com'']</ref> |

|||

{{main|Prehistoric Balkans|Moesia Superior|History of Medieval Kosovo|First Bulgarian Empire|History of Medieval Serbia}} |

|||

Dardania was conquered by Rome in the late 1st century B.C. and gave the [[Roman Empire]] some of its most outstanding emperors, including [[Constantine the Great]]. Christianity was spread in the country in its initial phases, while individuals like [[Nicetas of Remesiana|Niketas Dardani]], authored the early Christian hymnals. |

|||

Kosovo was a part of the antique [[Illyrians|Illyrian]]-[[Thracians|Thracian]] region of ''Dardania''. The Illyrians were conquered by Rome in the late 1st century BC and became part of [[Moesia Superior]] in AD 87. During the Great Migrations of peoples, [[Slavs]] or in precise, [[Serbs]], colonized it since the first half of the [[7th century]]. A part of the [[Byzantine empire]] it was conquered by the Bulgarians in the 850s. As the center of Slavic resistance to Constantinople in the region, it often switched between Serbian and Bulgarian rule on one hand and Byzantine on the other until the Serb principality of [[Rascia]] conquered it by the end of the [[11th century]]. |

|||

Following the [[Migration Period|barbarian invasions]] between the 5th and 8th century, Dardania became a safe haven for the preservation of Illyrian culture and language as well as the heritage of the Romanized population, and remained part of the Byzantine empire.<ref>[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R0tGOdHl7_0 WatchMojo, "The Illyrian Empire," ''Youtube'']</ref> In the 9th century, Dardania was conquered by the [[First Bulgarian Empire|Bulgarian empire]]. Later it was briefly returned to the Byzantines, before the [[Serbia]]n invasion in the late 12th century. In the next 100 years, the Serbs established their rule over Kosovo. During this time, the seat of the [[Serbian Orthodox Church]] was moved to [[Peja]],<ref>Noel Malcolm, ''Kosovo: A Short History'' (UP: New York, 2003) 50.</ref> while the natural resources allowed for a further expansion of the Serbian state. With the creation of a Serbian empire in the 1346 century, Dardania became a central geographical unit of the Serbian state. This fact and the presence of the Serbian Orthodoxy in the region has given rise to the Serbian cultural belief regarding Kosovo as the “cradle of the Serbian civilization.” |

|||

Fully absorbed into the Serbian Kingdom until the end of the [[12th century|12th]], it became the secular and spiritual center of the [[History of Medieval Serbia|Serbian medieval state]] of the [[House of Nemanjić|Nemanyiden]] dynasty in the [[13th century]], with the Patriarchate of the Serbian Orthodox Church in [[Peć]], while [[Prizren]] was the secular center. The zenith was reached with the formation of a [[Serbian Empire]] in 1346, which after 1371 transformed from a centralized absolutist medieval monarchy to a feudal realm. Kosovo became the hereditary land of the [[House of Branković]] and [[Vučitrn]] and [[Priština]] flourished. |

|||

In 1389, in the famous [[Battle of Kosovo]] a coalition of Christian armies including Serbs, Albanians, Bosnians and Hungarians, led by the Serbian prince [[Lazar Hrebljanovic]] was defeated by the [[Ottoman Turks]], who finally took control of the territory in [[1455]]. During the intervening years, some Serbian lords were granted the power to rule as vassals of the Ottoman Sultan, who used them as a means of quelling liberation movements from any of the Balkan nations. In the [[Battle of Kosovo (1448)|Second Battle of Kosovo]], the Turkish vassal, [[Djuradj Brankovic]], barricaded the Albanian leader [[Gjergj Kastrioti]] from joining with the Hungarian army of [[Janos Hunyadi]], who faced a weighty defeat. |

|||

In 1389 the joint forces under Prince [[Lazar Hrebeljanović]] were defeated in the epic [[Battle of Kosovo]], which became a very significant national-romantic event in Serbian history. In 1402 a [[Serbian Despotate]] was raised and Kosovo became its richest territory, famous for mines. During the first fall of Serbia [[Novo Brdo]] and Kosovo offered last resistance to the invading Ottomans in 1441, in 1455 it was finally and fully conquered by the Ottoman Empire. |

|||

=== |

===Ottoman rule=== |

||

{{ |

{{seealso|Vilayet of Kosovo}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{see|Vilayet of Kosovo|History of Ottoman Serbia}} |

|||

The Ottoman conquest of Kosovo was a major achievement for the Turks, as the Kosovar rich minerals would prove a great asset to their empire. The establishment of Ottoman institutions in Kosovo brought about a new era. Heavy religiously-selective taxation and education of the Kosovar aristocracy in Ottoman schools led to a mass conversion of the Christian population into [[Islam]]. The new religion was embraced by approximately two-thirds of the Albanians and a portion of the Slavs, while it slightly improved their status by ruling out threats of annihilation, it did not eliminate the struggle against the Ottoman regime.<ref>Ferid Duka, "Ndryshime në strukturën fetare të popullit shqiptar," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 117-118.</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Turkish existence in Yugoslavian territories goes back as early as to the 5th century with immigrations of Avar, Pecenek, Oghuz and Kuman tribes. <ref>http://www.axisglobe.com/article.asp?article=540</ref> Systematic settlement began however after the Ottoman conquest during the 14th century. |

|||

In 1389, Ottomans defeated Serbians and conquered Kosovo. See [[Battle of Kosovo]]. Turks started to settle down in the region according to the Ottoman traditions. Today, amongst many only 622 Ottoman buildings in Kosova are left, which are mostly in need of restoration. <ref>http://www.kapidergisi.com/dekorasyon-1827-turkiye_Balkanlar%E2%80%98daki_Osmanli_Eserlerini_Restore_Ettirecek-kapi.html</ref> |

|||

[[Image:SINPASHA.JPG]] |

|||

Kosovo was a typical redoubt of defiant people who fought against the new regime in quest for their national liberty. As a result, many Albanian highlanders retained some autonomy and were allowed to apply their customary law (mainly the [[Kanun|Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini]]). Nevertheless, examples of Ottoman attempts to give an end to this practice are abundant; the heroine Nora of the Kelmendi clan earned a distinguished place in Kosovar history by assassinating the Ottoman leader in Kosovo.<ref>Ferid Duka, "Lufta çlirimtare kundër sundimit osman (shek. XVI-XVII)," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 111.</ref> |

|||

The [[Ottoman Empire|Ottomans]] brought [[Islamisation]] with them, particularly in towns, and later also created the [[Vilayet of Kosovo]] as one of the Ottoman territorial entities. Kosovo was taken by the Austrian forces during the Great War of [[1683]]–[[1699]] with help of 5,000 Albanians and their leader, the [[Catholic]] [[Archbishop]] [[Pjetër Bogdani]]. In [[1690]], the [[Serbian Patriarch of Peć]] [[Arsenije III]], who previously escaped a certain death, led 37,000 families from Kosovo to evade [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] wrath, since Kosovo had just been retaken by the Ottomans. The people who followed him were mostly [[Serbs]], but they were likely followed by other ethnic groups. Due to the oppression from the Ottomans, other migrations of Orthodox people from the Kosovo area continued throughout the [[18th century]]. It is also noted that some [[Serbs]] adopted [[Islam]], while some even gradually fused with other groups, predominantly Albanians, adopting their culture and even language, essentially leaving a predominantly Islamic presence in Kosovo.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} |

|||

During the Ottoman period, nonetheless, there was recorded a great amount of endeavors to promote the Albanian language and culture. The Catholic cleric who authored the earliest known Albanian book, [[Gjon Buzuku]], is believed to have been of Kosovar origin. Moreover, the Catholic bishop, [[Pjetër Bogdani]], a native of Kosovo, published his classic ''Band of the Prophets'' in 1686, and later headed the anti-Ottoman movement. His engagement in the national cause culminated in 1689, when he raised a 20,000-member army comprised of Christian and Muslim Albanians, who joined the Austrians in their war against Turkey. The campaign resulted in a brief liberation of Kosovo, but after a plague breakout among Austrians and Kosovars, the Turks soon recovered all their lost areas. Bogdani himself died in December 1689, while his remains were inhumanely exhumed by Turks and Tatars and fed to dogs.<ref> [http://www.albanianliterature.net/authors1/AA1-01.html Pjetër Bogdani, biography by R. Elsie, ''Albanian Literature'']</ref> The loss had a negative impact on the wellbeing all inhabitants of Kosovo, whose liberation was not realized in an 18th-century Austrian endeavor either. |

|||

In 1766, the Ottomans abolished the [[Patriarchate of Peć]] and the position of [[Christians]] in Kosovo was greatly reduced. All previous privileges were lost, and the Christian population had to suffer the full weight of the Empire's extensive and losing wars.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} |

|||

=== |

===Albanian national movement=== |

||

{{main|20th century history of Kosovo}} |

|||

The Albanian national movement was inspired by various reasons. Besides from the National Renaissance that had been promoted by Albanian activists, political reasons were a contributing factor. In the 1870s the Ottoman Empire experienced a tremendous contraction in territory and defeats in wars against Slavic monarchies of Europe. During the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish war, the Serbian troops invaded the northeastern part of the province of Kosovo [[Albanian exodus|deporting]] 160,000 ethnic Albanians from 640 localities. Furthermore, the signing of the [[Treaty of San Stefano]] marked the beginning of a difficult situation for the Albanian people in the Balkans, whose lands were to be ceded from Turkey to Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria.<ref>Hysni Myzyri, "Kriza lindore e viteve 70 dhe rreziku i copëtimit të tokave shqiptare," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 151.</ref><ref> [http://historia.shqiperia.com/rilindja/kreu_5.php Historia e Shqipërisë, “Kreu V: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit,” ''Shqiperia.com'']</ref><ref>[http://www.hrw.org/reports/2001/kosovo/undword-11A.html HRW, " Prizren Municipality," ''UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo'']</ref> |

|||

{{splitsection|20th century history of Kosovo}} |

|||

{{Shorten}} |

|||

In 1871, a massive Serbian meeting was held in Prizren, at which the possible retaking and reintegration of Kosovo and the rest of "Old Serbia" was discussed, as the [[History of Serbia|Principality of Serbia]] itself had already made plans for expansions into Ottoman territory. Albanian refugees from the territories conquered in the 1876–1877 Serbo-Turkish war and the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish war became known as ''[[muhajir (Albania)|muhaxher]]'', meaning 'refugee', from [[Arabic]] ''[[muhajir]]''. Their descendants still have the same surname, ''Muhaxheri''. It is estimated that 200,000 to 400,000 Serbs were cleansed out of the [[Vilayet of Kosovo]] between 1876 and 1912 by Turks and their Albanian allies, especially during the [[Greco-Turkish War (1897)|Greek-Ottoman War]] in 1897.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} |

|||

Fearing the partitioning of Albanian-inhabited lands among the newly founded Balkan kingdoms, the Albanians established their [[League of Prizren]] on [[June 10]], [[1878]], three days prior to the Congress of Berlin that would revise the decisions of San Stefano.<ref>Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 104-116.</ref> Though the League was founded with the support of the Sultan who hoped for the preservation of Ottoman territories, the Albanian leaders were quick and effective enough to turn it into a national organization and eventually into a government. The League had the backing of the [[Arbëreshë|Italo-Albanian]] community and had well developed into a unifying factor for the religiously-diverse Albanian people. During its three years of existence the League sought the creation of an Albanian autonomous state within the Ottoman Empire, raised an army and fought a defensive war. In 1881 a provisional government was formed to administer Albania under the presidency of [[Ymer Prizreni]], assisted by prominent ministers such as [[Abdyl Frashëri]] and [[Sulejman Vokshi]]. Nevertheless, military intervention from the Balkan states, the Great Powers as well as Turkey divided the Albanian troops in three fronts, which brought about the end of the League.<ref>Hysni Myzyri, "Kreu VIII: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit (1878-1881)," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 149-172.</ref><ref> [http://historia.shqiperia.com/rilindja/kreu_5.php Historia e Shqipërisë, “Kreu V: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit” Shqiperia.com]</ref><ref>Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 104-116.</ref> |

|||

In 1878, a Peace Accord was drawn that left the cities of Priština and [[Kosovska Mitrovica]] under civil Serbian control, and outside the jurisdiction of the Ottoman authorities, while the rest of Kosovo would be under Ottoman control.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} In response, the Albanians formed the nationalistic and conservative [[League of Prizren]] later the same year. Over three hundred Albanian leaders from Kosovo and western Macedonia gathered and discussed the urgent issues concerning protection of Albanian-populated regions from being divided among neighbouring countries. The League was supported by the Ottoman Sultan because of its Pan-Islamic ideology and political aspirations of a [[Greater Albania|unified Albanian people]] under the Ottoman umbrella.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} The movement gradually became anti-Christian, and spread great anxiety among Christian Albanians and especially among Christian Serbs.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} As a result, more and more Serbs left Kosovo, going northward.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} Serbia complained to the World Powers that the promised territories were not being held, because the Ottomans were hesitating to do that. The World Powers put pressure on the Ottomans, and in 1881, the Ottoman Army began fighting the Albanian forces. The Prizren League created a Provisional Government with a President, Prime Minister (Ymer Prizreni), Minister of War (Sylejman Vokshi) and Foreign Minister (Abdyl Frashëri). After three years of war, the Albanians were defeated. Many of the leaders were executed and imprisoned. The subsequent Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 restored most Albanian lands to Ottoman control, but the Serbian forces had to retreat from Kosovo, along with some Serbs that were expelled as well. By the end of the 19th century, the Albanians had replaced the Serbs as the dominant people in Kosovo.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} |

|||

Kosovo was yet home to other Albanian organizations, the most important being the [[League of Peja]], named after the city in which it was founded in 1899. It was led by [[Haxhi Zeka]], a former member of the League of Prizren and shared a similar platform in quest for an autonomous Albania. The League ended its activity in 1900 after an armed conflict with the Ottoman forces. Zeka was assassinated by a Serbian agent in 1902 with the backing of the Ottoman authorities.<ref>Hysni Myzyri, "Kreu VIII: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit (1878-1881)," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 182-185.</ref> |

|||

In 1908, the Sultan brought a new democratic decree that was valid only for Turkish speakers. As the vast majority in Kosovo spoke Albanian or Serbian, the Kosovar population was very unhappy. The Young Turk movement supported a centralist rule, and opposed any sort of autonomy desired by Kosovars, particularly the Albanians. In 1910, an Albanian uprising spread from Priština and lasted until the Ottoman Sultan's visit to Kosovo in June of 1911. The aim of the League of Prizren was to unite the four Albanian Vilayets by merging the majority of Albanian inhabitants within the Ottoman Empire into one Albanian state. However, at that time Serbs had made up about 25% of the whole Vilayet of Kosovo's overall population, and they were opposing Albanian rule along with Turks and other Slavs in Kosovo, thus hindering the Albanian movements from occupying Kosovo.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} |

|||

===Independence of Albania and the Balkan Wars=== |

|||

The demands of the [[Young Turks]] in early 20th century sparked support from the Albanians, who were hoping for a betterment of their national status, primarily recognition of their language for use in offices and education.<ref>Hysni Myzyri, "Lëvizja kombëtare shqiptare dhe turqit e rinj," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 191.</ref><ref>Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 140-160.</ref> In 1908, 20,000 armed Albanian peasants gathered in [[Ferizaj]] to prevent any foreign intervention, while their leaders, [[Bajram Curri]] and [[Isa Boletini]], sent a telegram to the sultan demanding the promulgation of a constitution and the opening of the parliament. |

|||

The Albanians did not receive any of the promised benefits from the Young Turkish victory. Considering this, an unsuccessful uprising was organized by Albanian highlanders in Kosovo in February 1909. The adversity escalated after the takeover of the Turkish government by an oligarchic group later that year. In April 1910, armies led by [[Idriz Seferi]] and Isa Boletini rebelled against the Turkish troops, but were finally forced to withdraw after having caused many casualties amongst the enemy.<ref>Hysni Myzyri, "Kryengritjet shqiptare të viteve 1909-1911," ''Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme'' (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 195-198.</ref> |

|||

{{Refimprove|section|date=February 2008}} |

|||

==== Balkan Wars ==== |

|||

[[Image:Balkan Wars Boundaries.jpg|thumb|Boundaries on the Balkans after the [[First Balkan War|First]] and [[Second Balkan War]].]] |

[[Image:Balkan Wars Boundaries.jpg|thumb|Boundaries on the Balkans after the [[First Balkan War|First]] and [[Second Balkan War]].]] |

||

Revision as of 09:27, 24 February 2008

Republic of Kosovo | |

|---|---|

Location of Kosovo on the European continent | |

| Capital and largest city | Pristina |

| Official languages | Albanian, Serbian |

| Recognised regional languages | Turkish, Gorani, Romani, Bosnian |

| Ethnic groups (2007) | 92% Albanians 5.3% Serbs 2.7% others [1] |

| Demonym(s) | Kosovar |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Fatmir Sejdiu (LDK) | |

| Hashim Thaçi (PDK) | |

| Jakup Krasniqi (PDK) | |

| Independence1 from Serbia | |

• Declared | 17 February 2008 |

| by 17 countries [2][3][4] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,887 km2 (4,203 sq mi) (166) |

• Water (%) | n/a |

| Population | |

• 2007 estimate | 1,900,000[5] (141) |

• 1991 census | 1,956,1963 |

• Density | 220/km2 (569.8/sq mi) (55) |

| Currency | Euro (€)2 (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Calling code | None assigned |

| Internet TLD | None assigned |

| |

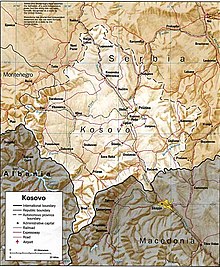

Kosovo (Albanian: Kosova or Kosovë, Serbian: Косово, Kosovo, Turkish: Kosova, see: Names of Kosovo), officially the Republic of Kosovo (Albanian: Republika e Kosovës, Serbian: Република Косово, Republika Kosovo), is a partially recognized landlocked republic in southeastern Europe, formerly a part of the Republic of Serbia. It has a population of about two million people, predominantly ethnic Albanians, with smaller populations of Serbs, Romani people, Goranis, Bosniaks, Turks and other ethnic communities. Pristina is the capital and largest city. Kosovo borders Montenegro to the west, Albania to the southwest, Republic of Macedonia to the south and Serbia to the north and east.

Following the Kosovo War in 1999, United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 placed Kosovo under the authority of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), with security provided by the NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR), and legally reaffirmed Serbia's sovereignty over the region and committed the UN Member States to its territorial integrity. After UN-sponsored negotiations failed to reach a consensus on an acceptable constitutional status, Kosovo's provisional government unilaterally declared independence from Serbia on 17 February 2008[6] and receiving partial international recognition as a sovereign state (notably from the United States and some major European countries).

Kosovo's sovereignity is disputed by Serbia, Russia, China, Spain, Romania, Slovakia, Greece, Cyprus and other nations. The official position of these countries is that Kosovo is a Serbian province under ad interim UN control , formally known as Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija (Serbian: Аутономна покрајина Косово и Метохија, Autonomna pokrajina Kosovo i Metohija, also Космет, Kosmet; Albanian: Krahina Autonome e Kosovës dhe Metohisë).

History

Ancient and medieval periods

Kosovo was known in antiquity and up to the 19th century as Dardania[7] (from Albanian word dardhë = pear; literally Pearland) after the Illyrian tribe Dardani.[8][9] Historical sources mention a Kingdom of Dardania as early as 4th century B.C., which included Kosovo and parts of surrounding areas.[10] Prominent kings include Longarus, Monunius, and Bato, who engaged in frequent wars against Macedon and achieved numerous successful victories.[11] There is also an account of wars with the Celts. Dardania was well-known for its gold resources and ancient writings describe the Dardani as fine producers of jewels. Major cities included Damastion, Naissus (Nis, Serbia), Scupi (Skopje, Macedonia), and Ulpiana.[12]

Dardania was conquered by Rome in the late 1st century B.C. and gave the Roman Empire some of its most outstanding emperors, including Constantine the Great. Christianity was spread in the country in its initial phases, while individuals like Niketas Dardani, authored the early Christian hymnals.

Following the barbarian invasions between the 5th and 8th century, Dardania became a safe haven for the preservation of Illyrian culture and language as well as the heritage of the Romanized population, and remained part of the Byzantine empire.[13] In the 9th century, Dardania was conquered by the Bulgarian empire. Later it was briefly returned to the Byzantines, before the Serbian invasion in the late 12th century. In the next 100 years, the Serbs established their rule over Kosovo. During this time, the seat of the Serbian Orthodox Church was moved to Peja,[14] while the natural resources allowed for a further expansion of the Serbian state. With the creation of a Serbian empire in the 1346 century, Dardania became a central geographical unit of the Serbian state. This fact and the presence of the Serbian Orthodoxy in the region has given rise to the Serbian cultural belief regarding Kosovo as the “cradle of the Serbian civilization.”

In 1389, in the famous Battle of Kosovo a coalition of Christian armies including Serbs, Albanians, Bosnians and Hungarians, led by the Serbian prince Lazar Hrebljanovic was defeated by the Ottoman Turks, who finally took control of the territory in 1455. During the intervening years, some Serbian lords were granted the power to rule as vassals of the Ottoman Sultan, who used them as a means of quelling liberation movements from any of the Balkan nations. In the Second Battle of Kosovo, the Turkish vassal, Djuradj Brankovic, barricaded the Albanian leader Gjergj Kastrioti from joining with the Hungarian army of Janos Hunyadi, who faced a weighty defeat.

Ottoman rule

The Ottoman conquest of Kosovo was a major achievement for the Turks, as the Kosovar rich minerals would prove a great asset to their empire. The establishment of Ottoman institutions in Kosovo brought about a new era. Heavy religiously-selective taxation and education of the Kosovar aristocracy in Ottoman schools led to a mass conversion of the Christian population into Islam. The new religion was embraced by approximately two-thirds of the Albanians and a portion of the Slavs, while it slightly improved their status by ruling out threats of annihilation, it did not eliminate the struggle against the Ottoman regime.[15]

Kosovo was a typical redoubt of defiant people who fought against the new regime in quest for their national liberty. As a result, many Albanian highlanders retained some autonomy and were allowed to apply their customary law (mainly the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini). Nevertheless, examples of Ottoman attempts to give an end to this practice are abundant; the heroine Nora of the Kelmendi clan earned a distinguished place in Kosovar history by assassinating the Ottoman leader in Kosovo.[16]

During the Ottoman period, nonetheless, there was recorded a great amount of endeavors to promote the Albanian language and culture. The Catholic cleric who authored the earliest known Albanian book, Gjon Buzuku, is believed to have been of Kosovar origin. Moreover, the Catholic bishop, Pjetër Bogdani, a native of Kosovo, published his classic Band of the Prophets in 1686, and later headed the anti-Ottoman movement. His engagement in the national cause culminated in 1689, when he raised a 20,000-member army comprised of Christian and Muslim Albanians, who joined the Austrians in their war against Turkey. The campaign resulted in a brief liberation of Kosovo, but after a plague breakout among Austrians and Kosovars, the Turks soon recovered all their lost areas. Bogdani himself died in December 1689, while his remains were inhumanely exhumed by Turks and Tatars and fed to dogs.[17] The loss had a negative impact on the wellbeing all inhabitants of Kosovo, whose liberation was not realized in an 18th-century Austrian endeavor either.

Albanian national movement

The Albanian national movement was inspired by various reasons. Besides from the National Renaissance that had been promoted by Albanian activists, political reasons were a contributing factor. In the 1870s the Ottoman Empire experienced a tremendous contraction in territory and defeats in wars against Slavic monarchies of Europe. During the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish war, the Serbian troops invaded the northeastern part of the province of Kosovo deporting 160,000 ethnic Albanians from 640 localities. Furthermore, the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano marked the beginning of a difficult situation for the Albanian people in the Balkans, whose lands were to be ceded from Turkey to Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria.[18][19][20]

Fearing the partitioning of Albanian-inhabited lands among the newly founded Balkan kingdoms, the Albanians established their League of Prizren on June 10, 1878, three days prior to the Congress of Berlin that would revise the decisions of San Stefano.[21] Though the League was founded with the support of the Sultan who hoped for the preservation of Ottoman territories, the Albanian leaders were quick and effective enough to turn it into a national organization and eventually into a government. The League had the backing of the Italo-Albanian community and had well developed into a unifying factor for the religiously-diverse Albanian people. During its three years of existence the League sought the creation of an Albanian autonomous state within the Ottoman Empire, raised an army and fought a defensive war. In 1881 a provisional government was formed to administer Albania under the presidency of Ymer Prizreni, assisted by prominent ministers such as Abdyl Frashëri and Sulejman Vokshi. Nevertheless, military intervention from the Balkan states, the Great Powers as well as Turkey divided the Albanian troops in three fronts, which brought about the end of the League.[22][23][24]

Kosovo was yet home to other Albanian organizations, the most important being the League of Peja, named after the city in which it was founded in 1899. It was led by Haxhi Zeka, a former member of the League of Prizren and shared a similar platform in quest for an autonomous Albania. The League ended its activity in 1900 after an armed conflict with the Ottoman forces. Zeka was assassinated by a Serbian agent in 1902 with the backing of the Ottoman authorities.[25]

Independence of Albania and the Balkan Wars

The demands of the Young Turks in early 20th century sparked support from the Albanians, who were hoping for a betterment of their national status, primarily recognition of their language for use in offices and education.[26][27] In 1908, 20,000 armed Albanian peasants gathered in Ferizaj to prevent any foreign intervention, while their leaders, Bajram Curri and Isa Boletini, sent a telegram to the sultan demanding the promulgation of a constitution and the opening of the parliament. The Albanians did not receive any of the promised benefits from the Young Turkish victory. Considering this, an unsuccessful uprising was organized by Albanian highlanders in Kosovo in February 1909. The adversity escalated after the takeover of the Turkish government by an oligarchic group later that year. In April 1910, armies led by Idriz Seferi and Isa Boletini rebelled against the Turkish troops, but were finally forced to withdraw after having caused many casualties amongst the enemy.[28]

In 1912, during the Balkan Wars, most of Kosovo was taken by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the region of Metohija (Albanian: Dukagjini Valley) was taken by the Kingdom of Montenegro. An exodus of the local Albanian population occurred. This was described by Leon Trotsky, who was a reporter for the Pravda newspaper at the time. The Serbian authorities planned a recolonization of Kosovo.[29] Numerous colonist Serb families moved into Kosovo, equalizing the demographic balance between Albanians and Serbs. Many Albanians fled into the mountains, and numerous Albanian and Turkish houses were razed. The reconquest of Kosovo was described as retribution for the 1389 Battle of Kossovo. At the Conference of Ambassadors in London in 1912, presided over by British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, the Kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro were granted sovereignty over Kosovo.[citation needed]

World War I

In the winter of 1915-1916, during World War I, Kosovo saw a large exodus of the Serbian army, which became known as the Great Serbian Retreat. Defeated and worn out in battles against Austro-Hungarians, they had no other choice than to retreat, as Kosovo was occupied by Bulgarians and Austro-Hungarians. The Albanians joined and supported the Central Powers. As opposed to Serbian schools, numerous Albanian schools were opened during the 'occupation' (the majority Albanian population considered it a liberation). Allied ships were awaiting Serbian people and soldiers at the banks of the Adriatic sea, and the path leading them there went across Kosovo and Albania. Tens of thousands of soldiers died of starvation, extreme weather and Albanian reprisals[citation needed] as they were approaching the Allies in Corfu and Thessaloniki, amassing a total of 100,000 dead retreaters.[citation needed] Transported away from the front lines, the Serbian army managed to treat many wounded and ill soldiers and get some rest. Refreshed and regrouped, it decided to return to the battlefield. In 1918, the Serbian Army pushed the Central Powers out of Kosovo. During Serbian control of Kosovo, the Serbian Army committed atrocities against the population in revenge.[citation needed] Serbian Kosovo was unified with Montenegrin Metohija, as Montenegro subsequently joined the Kingdom of Serbia. After World War I ended, the Monarchy was then transformed into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians (Serbo-Croatian: Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca, Albanian: Mbretëria Serbe, Kroate, Sllovene) on 1 December 1918, gathering territories gained in victory.[citation needed]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia and World War II

The 1918–1929 period of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians witnessed a rise of the Serbian population in the region and a decline in the non-Serbian population. Within the Kingdom, Kosovo was split into four counties, three being a part of the entity of Serbia: Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija; and one of Montenegro: northern Metohija. However, the new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three Areas of the Kingdom: Kosovo, Rascia and Zeta. In 1921 the Albanian elite lodged an official protest of the government to the League of Nations, claiming that 12,000 Albanians had been killed and over 22,000 imprisoned since 1918, and seeking a unification of Albanian-populated lands. As a result, an armed Kachak resistance movement was formed, whose main goal was to unite Albanian-populated areas of the Kingdom with Albania.[citation needed]

In 1929, the Kingdom was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the territories of Kosovo were reorganised among the Banate of Zeta, the Banate of Morava and the Banate of Vardar. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia lasted until the World War II Axis invasion of 1941.[citation needed]

The greater part of Kosovo became a part of Italian-controlled Fascist Albania, and smaller bits by the Tsardom of Bulgaria and Nazi German-occupied Kingdom of Serbia. During the fascist occupation of Kosovo by Albanians, until August 1941 alone, over 10,000 Serbs were killed and between 80,000 and 100,000 Serbs were expelled, while roughly the same number of Albanians from Albania were brought to settle in these Serbian lands.[30]

Mustafa Kruja, the Prime Minister of Albania, was in Kosovo in June 1942, and at a meeting with the Albanian leaders of Kosovo, said: "We should endeavor to ensure that the Serb population of Kosovo be – the area be cleansed of them and all Serbs who had been living there for centuries should be termed colonialists and sent to concentration camps in Albania. The Serb settlers should be killed."[31][32]

Prior to the surrender of Fascist Italy in 1943, German forces took over direct control of the region. Following numerous uprisings of Partisans led by Fadil Hoxha, Kosovo was liberated beginning in 1944 with the help of the Albanian partisans of the Comintern, and became a province of Serbia within the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

Kosovo in the Second Yugoslavia

The province was first formed in 1945 as the Autonomous Kosovo-Metohian Area to protect its regional Albanian majority within the People's Republic of Serbia as a member of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia under the leadership of the former Partisan leader, Josip Broz Tito, but with no actual autonomy. After Yugoslavia's name change to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia's to the Socialist Republic of Serbia in 1953, Kosovo gained internal autonomy in the 1960s.

Tito pursued a policy of weakening Serbia, as he believed that a "Weak Serbia equals a strong Yugoslavia". In the 1974 constitution, the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo's government received higher powers, including the highest governmental titles — President and Prime Minister - and a seat in the Federal Presidency, which made it a de facto Socialist Republic within the Federation, but remaining a Socialist Autonomous Province within the Socialist Republic of Serbia. (Similar rights were extended to Vojvodina. In Kosovo, Serbo-Croatian, Albanian and Turkish were defined as official languages on the provincial level.

In the 1970s, an Albanian nationalist movement pursued full recognition as a Republic within the Yugoslav Federation, while extreme elements aimed for full-scale independence. The ethnic balance of Kosovo tilted as the number of Albanians tripled, rising from almost 75% to over 90%, but the number of Serbs barely increased, dropping from 15% to 8% of the total population. Even though Kosovo was the least developed area of the former Yugoslavia, the living and economic prospects and freedoms were far greater than under the totalitarian Hoxha regime in Albania.

Beginning in March 1981, Kosovar Albanian students organized protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia. Those protests rapidly escalated into violent riots "involving 20,000 people in six cities"[33] that were harshly contained by the Yugoslav government. During the 1980s, ethnic tensions continued, with frequent violent outbreaks against Serbs and Yugoslav state authorities, resulting in increased emigration of Kosovo Serbs and other ethnic groups.[34][35] The Yugoslav leadership tried to suppress protests of Kosovo Serbs seeking protection from ethnic discrimination and violence.[36]

In 1986, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) was working on a document that later would be known as the SANU Memorandum, a warning to the Serbian President and Assembly of the existing crisis and where it would lead. An unfinished edition was filtered to the press. In the essay, SANU criticised the state of Yugoslavia, and made remarks that the only member state contributing at the time to the development of Kosovo and Macedonia (by then, the poorest territories of the Federation) was Serbia. According to SANU, Yugoslavia was suffering from ethnic strife and the disintegration of the Yugoslav economy into separate economic sectors and territories, which was transforming the federal state into a loose confederation.[37] On the other hand, some think that Slobodan Milošević used the discontent reflected in the SANU memorandum for his own political goals, during his rise to power in Serbia at the time.

Kosovo and the breakup of Yugoslavia

Inter-ethnic tensions continued to worsen in Kosovo throughout the 1980s. In particular, Kosovo's ethnic Serb community, a minority of Kosovo's population, complained about mistreatment from the Albanian majority. Miloševic capitalized on this discontent to consolidate his own position in Serbia. Milošević was sent by Ivan Stabolić to meet with local leaders, because the local Serbs were threatening to organize a demonstration in Belgrade.[38] However, a large demonstration of Serbian nationalists had been organized to coincide with Milošević's arrival. When the demonstrators broke through the police cordon, the police got out their batons and the situation began to get ugly. At this point, Milošević went to a window and and declared "Nobody must ever again dare to beat these people." Afterwards, he agreed to listen to representatives of the Serbs who aired their grievances; this continued until the next morning. [39] From this moment on, Milošević used the issue of Kosovo in his rise to power.[40]

On June 28, 1989, Milošević delivered a speech in front of a large number of Serb citizens at the main celebration marking the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, held at Gazimestan. Many think that this speech helped Milošević consolidate his authority in Serbia.[41]

In 1989, Milošević, employing a mix of intimidation and political maneuvering, drastically reduced Kosovo's special autonomous status within Serbia. Soon thereafter, Kosovo Albanians organized a non-violent separatist movement, employing widespread civil disobedience, with the ultimate goal of achieving the independence of Kosovo. Kosovo Albanians boycotted state institutions and elections and established separate Albanian schools and political institutions. On July 2 1990, an unconstitutional Kosovo parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, although this was not recognized by Belgrade or any foreign states. Two years later, in 1992, the parliament organized an unofficial referendum that was observed by international organizations, but was not recognized internationally. With an 80% turnout, 98% voted for Kosovo to be independent.[citation needed]

The 1990s

The Republic of Kosova (Albanian: Republika e Kosovë) was a secessionist state proclaimed in 1991 by a parallel parliament representing the Ethnic Albanian population of Kosovo. During its peak it established its own parallel political institutions in opposition to the Serb-dominated institutions of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija. The Republic of Kosova was formally disbanded in 2000 when its institutions were replaced by the Joint Interim Administrative Structure established by the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). During its lifetime, the Republic of Kosova was only recognized by Albania.

The Kosovo War was a conflict between Serbian and Yugoslav security forces and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerilla group, supported by NATO and the Islamic mujahideen seeking secession from the former Yugoslavia.

In 1998 western interest increased and the Serbian authorities were forced to sign a unilateral cease-fire and partial retreat. Under an agreement devised by Richard Holbrooke, OSCE observers moved into Kosovo to monitor the ceasefire, while Yugoslav military forces partly pulled out of Kosovo. However, the ceasefire was systematically broken shortly thereafter by KLA forces, which again provoked harsh counterattacks by the Serbs. NATO intervention between March 24 and June 10 1999,[42] combined with continued skirmishes between Albanian guerrillas and Yugoslav forces resulted in a massive displacement of population in Kosovo.[43]

During the conflict 850 000 ethnic Albanians fled or were forcefully driven from Kosovo, several thousand were killed (the numbers and the ethnic distribution of the casualties are uncertain and highly disputed). An alleged 12,000-18,000 ethnic Albanians[44] and 3,000 Serbs are believed to have been killed during the conflict.According to uncorroborated media report up to 20,000 Kosovo Albanian women were allegedly raped during the Kosovo carnage.[45] 3,368 people are still missing, of which 2,500 are Albanian, 400 Serbs and 100 Roma.[46]

Recent history (1999 to present)

After the war ended, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1244 that placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration (UNMIK) and authorized KFOR, a NATO-led peacekeeping force. Resolution 1244 also delivered that Kosovo will have autonomy within Federal Republic of Yugoslavia[47] (today legal successor of Federal Republic of Yugoslavia is Republic of Serbia).

In 2001, UNMIK promulgated a Constitutional Framework for Kosovo that established the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government (PISG), including an elected Kosovo Assembly, Presidency and office of Prime Minister. Kosovo held its first free, Kosovo-wide elections in late 2001 (municipal elections had been held the previous year).

In March 2004, Kosovo experienced its worst inter-ethnic violence since the Kosovo War. The unrest in 2004 was sparked by a series of minor events that soon cascaded into large-scale riots.[48]

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244. The UN-backed talks, lead by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. Whilst progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[49]

In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution which proposes 'supervised independence' for the province. A draft resolution, backed by the United States, the United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council, was presented and rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[50] Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, had stated that it would not support any resolution which was not acceptable to both Belgrade and Kosovo Albanians.[51] Whilst most observers had, at the beginning of the talks, anticipated independence as the most likely outcome, others have suggested that a rapid resolution might not be preferable.[52]

After many weeks of discussions at the UN, the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council formally 'discarded' a draft resolution backing Ahtisaari's proposal on 20 July 2007, having failed to secure Russian backing. Beginning in August, a "Troika" consisting of negotiators from the European Union (Wolfgang Ischinger), the United States (Frank Wisner) and Russia (Alexander Botsan-Kharchenko) launched a new effort to reach a status outcome acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina. Despite Russian disapproval, the U.S., Britain, and France appeared likely to recognize Kosovar independence[53]. A declaration of independence by Kosovar Albanian leaders was postponed until the end of the Serbian presidential elections (4 February 2008). Most EU members and the US had feared that a premature declaration could boost support in Serbia for the ultra-nationalist candidate, Tomislav Nikolic.[54]

Declaration of Independence

The Kosovar Assembly approved a declaration of independence on 17 February 2008.[55] In a following day several countries (United States, Turkey, Albania, Austria, Germany, Italy, France, United Kingdom, Australia, etc.) announced their recognition, despite protests by Serbia in the UN Security Council.[56] Some countries are either undetermined, or will not recognize independence of Kosovo due to internal interests, or so as not to damage relations with Serbia, or for other reasons. Most of the these countries are located in the region (Croatia, Republic of Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Romania, Greece), but others are more remote (Russia, Spain, South Africa etc.).

Geography

Kosovo has an area of 10,887 square kilometers[57] (4,203 sq mi) and a population of about 2.2 million. The largest cities are Priština, the capital, with an estimated 170,000 inhabitants, Prizren in the south west with a population of 110,000, Peć in the west with 70,000, and Kosovska Mitrovica in the north with 70,000.

The climate in Kosovo is continental, with warm summers and cold and snowy winters. There are two main plains in Kosovo. The Metohija basin is located in the western part of the Kosovo, and the Plain of Kosovo occupies the eastern part.

Much of Kosovo's terrain is mountainous. The Šar Mountains are located in the south and south-east, bordering the Republic of Macedonia. This is one of the region's most popular tourist and skiing resorts, with Brezovica and Prevalac as the main tourist centers. Kosovo's mountainous area, including the highest peak Đeravica, at 2656 m above sea level, is located in the south-west, bordering Montenegro and Albania.

The Kopaonik mountains are located in the north. The central region of Drenica, Crnoljeva and the eastern part of Kosovo, known as Goljak, are mainly hilly areas. There are several notable rivers and lakes in Kosovo. The main rivers are the White Drin, running towards the Adriatic Sea, with the Erenik among its tributaries), the Sitnica, the South Morava in the Goljak area, and Ibar in the north. The main lakes are Gazivoda (380 million m³) in the north-western part, Radonjić (113 million m³) in the south-west part, Batlava (40 million m³) and Badovac (26 million m³) in the north-east part.

List of largest cities in Kosovo (with population figures for 2003-12-31):[58]

- Priština (Prishtina): 165,844

- Prizren : 107,614

- Uroševac (Ferizaj) : 71,758

- Kosovska Mitrovica : 68,929

- Đakovica (Gjakova) : 68,645

- Peć (Peja) : 68,551

- Gnjilane (Gjilan): 55,781

- Vučitrn (Vushtrri) : 39,642

- Podujevo : 37,203

Politics and governance

|

|---|

| Constitution and law |

In 1999, UN Security Council Resolution 1244 placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration pending a determination of Kosovo's future status. This Resolution entrusted the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) with sweeping powers to govern Kosovo, but also directed UNMIK to establish interim institutions of self-governance. Resolution 1244 permits Serbia no role in governing Kosovo and since 1999 Serbian laws and institutions have not been valid in Kosovo. NATO has a separate mandate to provide for a safe and secure environment.

In May 2001, UNMIK promulgated the Constitutional Framework, which established Kosovo's Provisional Institutions of Self-Government (PISG). The PISG replaced the Joint Interim Administrative Structure (JIAS) established a year earlier. Since 2001, UNMIK has been gradually transferring increased governing competencies to the PISG, while reserving some powers that are normally carried out by sovereign states, such as foreign affairs. Kosovo has also established municipal government and an internationally-supervised Kosovo Police Service.

According to the Constitutional Framework, Kosovo shall have a 120-member Kosovo Assembly. The Assembly includes twenty reserved seats: ten for Kosovo Serbs and ten for non-Serb minorities (Bosniaks, Roma, etc). The Kosovo Assembly is responsible for electing a President and Prime Minister of Kosovo.

The largest political party in Kosovo, the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), has its origins in the 1990s non-violent resistance movement to Miloševic's rule. The party was led by Ibrahim Rugova until his death in 2006. The two next largest parties have their roots in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA): the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) led by former KLA leader Hashim Thaci and the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK) led by former KLA commander Ramush Haradinaj. Kosovo publisher Veton Surroi formed his own political party in 2004 named "Ora." Kosovo Serbs formed the Serb List for Kosovo and Metohija (SLKM) in 2004, but have boycotted Kosovo's institutions and never taken their seats in the Kosovo Assembly.

In November 2001, the OSCE supervised the first elections for the Kosovo Assembly. After that election, Kosovo's political parties formed an all-party unity coalition and elected Ibrahim Rugova as President and Bajram Rexhepi (PDK) as Prime Minister.

After Kosovo-wide elections in October 2004, the LDK and AAK formed a new governing coalition that did not include PDK and Ora. This coalition agreement resulted in Ramush Haradinaj (AAK) becoming Prime Minister, while Ibrahim Rugova retained the position of President. PDK and Ora were critical of the coalition agreement and have since frequently accused the current government of corruption.

Ramush Haradinaj resigned the post of Prime Minister after he was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in March 2005. He was replaced by Bajram Kosumi (AAK). But in a political shake-up after the death of President Rugova in January 2006, Kosumi himself was replaced by former Kosovo Protection Corps commander Agim Ceku. Ceku has won recognition for his outreach to minorities, but Serbia has been critical of his wartime past as military leader of the KLA and claims he is still not doing enough for Kosovo Serbs. The Kosovo Assembly elected Fatmir Sejdiu, a former LDK parliamentarian, president after Rugova's death. Slaviša Petkovic, Minister for Communities and Returns, was previously the only ethnic Serb in the government, but resigned in November 2006 amid allegations that he misused ministry funds.[59][60] Today two of the total thirteen ministries in Kosovo's Government have ministers from the minorities. Branislav Grbic, ethnic Serb, leads Minister of Returns and Sadik Idriz, ethnic Bosnjak, leads Ministry of Health[61]

Parliamentary elections were held on 17 November 2007. After early results, Hashim Thaçi who was on course to gain 35 per cent of the vote, claimed victory for PDK, the Albanian Democratic Party, and stated his intention to declare independence. Thaci is likely to form a coalition with current President Fatmir Sejdiu's Democratic League which was in second place with 22 percent of the vote. The turnout at the election was particularly low with most Serbs refusing to vote.[62]

Health

Access to health care is free for all residents of Kosovo. Currently there is no health insurance, however, the Ministry of Health is in the process of preparing a legislative infrastructure, which is scheduled to be implemented in 2008.

There are hospitals in all major cities. A total of 6 regional hospitals provide tertiary health care, and family centers in small municipalities.

Medical Education is available at the University Clinical Center of Kosovo (UCCK), in Pristina.

Economy

Kosovo has one of the most under-developed economies in Europe, with a per capita income estimated at €1,565 (2004).[63] Despite substantial development subsidies from all Yugoslav republics, Kosovo was the poorest province of Yugoslavia.[64] Additionally, over the course of the 1990s a blend of poor economic policies, international sanctions, poor external commerce and ethnic conflict severely damaged the economy.[65]

Kosovo's economy remains weak. After a jump in 2000 and 2001, growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was negative in 2002 and 2003 and is expected to be around 3 percent 2004-2005, with domestic sources of growth unable to compensate for the declining foreign assistance. Inflation is low, while the budget posted a deficit for the first time in 2004. Kosovo has high external deficits. In 2004, the deficit of the balance of goods and services was close to 70 percent of GDP. Remittances from Kosovars living abroad accounts for an estimated 13 percent of GDP, and foreign assistance for around 34 percent of GDP.

Most economic development since 1999 has taken place in the trade, retail and the construction sectors. The private sector that has emerged since 1999 is mainly small-scale. The industrial sector remains weak and the electric power supply remains unreliable, acting as a key constraint. Unemployment remains pervasive, at around 40-50% of the labor force.[66]

UNMIK introduced de-facto an external trade regime and customs administration on September 3, 1999 when it set customs border controls in Kosovo. All goods imported in Kosovo face a flat 10% customs duty fee.[67] These taxes are collected from all Tax Collection Points installed at the borders of Kosovo, including those between Kosovo and Serbia.[68] UNMIK and Kosovo institutions have signed Free Trade Agreements with Croatia,[69] Bosnia and Herzegovina,[70] Albania and Republic of Macedonia.[67]

The Republic of Macedonia is Kosovo's largest import and export market (averaging €220 million and €9 million, respectively), followed by Serbia-Montenegro (€111 million and €5 million), Germany and Turkey.[71]

The euro is the official currency of Kosovo and used by UNMIK and the government bodies.[72] The Serbian dinar is used in the Serbian-populated parts.

The economy is hindered by Kosovo's still-unresolved international status, which has made it difficult to attract investment and loans.[73] The province's economic weakness has produced a thriving black economy in which smuggled petrol, cigarettes and cement are major commodities. The prevalence of official corruption and the pervasive influence of organised crime gangs has caused serious concern internationally. The United Nations has made the fight against corruption and organised crime a high priority, pledging a "zero tolerance" approach.

Demographics

According to the Kosovo in Figures 2005 Survey of the Statistical Office of Kosovo,[74][75][76] Kosovo's total population is estimated between 1.9 and 2.2 million in the following ethnic proportions:

Islam is the predominant religion, professed by most of the majority ethnic Albanian population, the Bosniak, Gorani, and Turkish communities, and some of the Roma/Ashkali/Egyptian community, although religion is not a significant factor in public life. Religious rhetoric was largely absent from public discourse in Muslim communities, mosque attendance was low, and public displays of conservative Islamic dress and culture were minimal. The Serb population, estimated at 100,000 to 120,000 persons, is largely Serbian Orthodox. Approximately 3 percent of ethnic Albanians are Roman Catholic. Catholic communities are concentrated around Catholic churches in Prizren, Klina, and Gjakova. Protestants make up less than 1 percent of the population and have small populations in most cities, with the largest concentration located in Pristina. There are no synagogues or Jewish institutions; there are reportedly two families whose members have Jewish roots. The number of atheists or those who do not practice any religion are difficult to determine, and estimates are largely unreliable. [77][78][79]

Ethnic Albanians in Kosovo have the largest population growth in Europe.[80][81] The people’s growth rate in Kosovo is 1.3%. Over an 82-year period (1921-2003) the population grew 4.6 times. If growth continues at such a pace, based on some estimations, the population will be 4.5 million by 2050.[82]

Administrative divisions

Kosovo, for administrative reasons, is considered as consisting of seven districts. North Kosovo maintains its own government, infrastructure and institutions by its dominant ethnic Serb population in the Mitrovica District, viz. in the Leposavic, Zvecan and Zubin Potok municipalities and the northern part of Kosovska Mitrovica.

Kosovo is also divided into 30 municipalities :

Culture

Music

Although in Kosovo the music is diverse (influenced to an extent by the cultures of the various regimes who controlled the region), authentic Albanian music (see World Music) and Serbian music do still exist. Albanian music is characterized by the use of the çiftelia (an authentic Albanian instrument), mandolin, mandola and percussion. In Kosovo, folk music is very popular alongside modern music. There are a number of folk singers and ensembles (both Albanian and Serbian). Classical music is also well known in Kosovo and has been taught at universities (at the University of Priština Faculty of Arts and the University of Priština at Kosovska Mitrovica Faculty of Arts) and several pre-college music schools

There are some notable music festivals in Kosovo:

- Rock për Rock - contains rock and metal music

- Polifest - contains all kinds of genres (usually hip hop and commercial pop)

- Showfest - contains all kinds of genres (usually hip hop and commercial pop)

- Videofest - contains all kinds of genres

- Kush Këndon Lutet Dy Herë - contains Christian music

- North City Jazz & Blues festival, an international music festival held annually in Zvečan (Albanian: Zveçani), near Kosovska Mitrovica,

Kosovo Radiotelevisions like RTK, 21 and KTV have their musical charts.

Sport

Several sports federations have been formed in Kosovo within the framework of Law No. 2003/24 "Law on Sport" passed by the Assembly of Kosovo in 2003. The law formally established a national Olympic Committee, regulated the establishment of sports federations and established guidelines for sports clubs. At present only some of the sports federations established have gained international recognition.

Federations that have so far gained membership or recognition by their international governing body:

Federations that have not yet gained international recognition:

- Basketball Federation of Kosovo

- Football Federation of Kosovo and the Kosovo national football team

- Olympic Committee of Kosovo

- Tennis Federation of Kosovo

References

- ^ Enti i Statistikës së Kosovës

- ^ US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice (2008-02-18). "U.S. Recognizes Kosovo as Independent State". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Britain, France recognise Kosovo". Associated Press. 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Castle, Stephen (2008-02-18). "Kosovo is Recognised by U.S., France and Britain". Retrieved 2008-02-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ See: UN estimate, Kosovo’s population estimates range from 1.9 to 2.4 million. The last two population census conducted in 1981 and 1991 estimated Kosovo’s population at 1.6 and 1.9 million respectively, but the 1991 census probably undercounted Albanians. The latest estimate in 2001 by OSCE puts the number at 2.4 Million.

- ^ BBC News: Kosovo MPs proclaim independence - February 17, 2008

- ^ Arthur Evans, “Some Observations on the Present State of Dardania,” R. Elsie ed., Albanian History

- ^ Noel Malcolm, Kosovo: A Short History (UP: New York, 2003) 31.

- ^ Aleksandar Stipcevic, Iliri, 30; Mirdita, Studime dardane, 7-46; Papazoglu, Central Balkan Tribes, 210-69 & "Dardanska onomastika"; Katicic, Ancient Languages, 179-81

- ^ Bep Jubani, "Mbretëria Dardane," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 26-29.

- ^ Bep Jubani, "Mbretëria Dardane," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 26-29.

- ^ Historia e Shqipërisë, “Mbretëria e Dardanisë: Territori dhe popullsia,” Shqiperia.com

- ^ WatchMojo, "The Illyrian Empire," Youtube

- ^ Noel Malcolm, Kosovo: A Short History (UP: New York, 2003) 50.

- ^ Ferid Duka, "Ndryshime në strukturën fetare të popullit shqiptar," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 117-118.

- ^ Ferid Duka, "Lufta çlirimtare kundër sundimit osman (shek. XVI-XVII)," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 111.

- ^ Pjetër Bogdani, biography by R. Elsie, Albanian Literature

- ^ Hysni Myzyri, "Kriza lindore e viteve 70 dhe rreziku i copëtimit të tokave shqiptare," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 151.

- ^ Historia e Shqipërisë, “Kreu V: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit,” Shqiperia.com

- ^ HRW, " Prizren Municipality," UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo

- ^ Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 104-116.

- ^ Hysni Myzyri, "Kreu VIII: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit (1878-1881)," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 149-172.

- ^ Historia e Shqipërisë, “Kreu V: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit” Shqiperia.com

- ^ Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 104-116.

- ^ Hysni Myzyri, "Kreu VIII: Lidhja Shqiptare e Prizrenit (1878-1881)," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 182-185.

- ^ Hysni Myzyri, "Lëvizja kombëtare shqiptare dhe turqit e rinj," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 191.

- ^ Г. Л. Арш, И. Г. Сенкевич, Н. Д. Смирнова «Кратая история Албании» (Приштина: Рилиндя, 1967) 140-160.

- ^ Hysni Myzyri, "Kryengritjet shqiptare të viteve 1909-1911," Historia e popullit shqiptar: për shkollat e mesme (Libri Shkollor: Prishtinë, 2002) 195-198.

- ^ Elsie, R. (ed.) (2002): "Gathering Clouds. The roots of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. Early twentieth-century documents". Dukagjini Balkan Books, Peja (Kosovo, Serbia). ISBN 9951-05-016-6

- ^ Krizman, Serge. "Massacre of the innocent Serbian population, committed in Yugoslavia by the Axis and its Satellite from April 1941 to August 1941". Map. Maps of Yugoslavia at War, Washington, 1943.

- ^ Bogdanović, Dimitrije. "The Book on Kosovo". 1990. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1985. page 2428.

- ^ Genfer, Der Kosovo-Konflikt, Munich: Wieser, 2000. page 158.

- ^ New York Times 1981-04-19, "One Storm has Passed but Others are Gathering in Yugoslavia"

- ^ Reuters 1986-05-27, "Kosovo Province Revives Yugoslavia's Ethnic Nightmare"

- ^ Christian Science Monitor 1986-07-28, "Tensions among ethnic groups in Yugoslavia begin to boil over"

- ^ New York Times 1987-06-27, "Belgrade Battles Kosovo Serbs"

- ^ SANU (1986): Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Memorandum. GIP Kultura. Belgrade.

- ^ The Serbs Tim Judah p162

- ^ Yugoslavia's Ethnic Nightmare. Ed Jasminka Udovićka and James Ridgeway p82

- ^ The Serbs Tim Judah p162

- ^ The Economist, June 05, 1999, U.S. Edition, 1041 words, "What's next for Slobodan Milošević?"

- ^ "Operation Allied Force". NATO. 2006-05-26. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Larry Minear, Ted van Baarda, Marc Sommers (2000). "NATO and Humanitarian Action in the Kosovo Crisis" (PDF). Brown University.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Kosovo independence". The Observer. Guardian News and Media. 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ "Rape victims' babies pay the price of war". The Observer. Guardian News and Media. 2000-04-16. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ "3,000 missing in Kosovo". BBC News. 2000-06-07. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ "RESOLUTION 1244 (1999)". BBC News. 1999-06-17. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ U.S State Department Report, published in 2007.

- ^ "UN frustrated by Kosovo deadlock ", BBC News, October 9, 2006.

- ^ Southeast European Times (29/06/2007). "Russia reportedly rejects fourth draft resolution on Kosovo status".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Southeast European Times (09/07/07). "UN Security Council remains divided on Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ James Dancer (30/03/07). "A long reconciliation process is required". Financial Times.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Simon Tisdall (13/11/07). "Bosnian nightmare returns to haunt EU". The Guardian.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6386467.stm

- ^ "Kosovo MPs proclaim independence", BBC News Online, 17 February 2008

- ^ "Recognition for new Kosovo grows", BBC News Online, 18 February 2008

- ^ Independent Commission for Mines and Minerals. "Welcome to the Independent Commission for Mines and Minerals (ICMM), Kosovo".

- ^ City Population. "Kosovo".

- ^ "Kosovo: Serb minister resigns over misuse of funds ", Adnkronos international (AKI), November 27, 2006

- ^ "Sole Kosovo Serb cabinet minister resigns: PM ", Agence France-Presse (AFP), November 24, 2006.

- ^ Fillimi

- ^ EuroNews: Ex-guerrilla chief claims victory in Kosovo election. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ^ The World Bank (2006). "Kosovo Brief 2006".

- ^ Christian Science Monitor 1982-01-15, "Why Turbulent Kosovo has Marble Sidewalks but Troubled Industries"

- ^ The World Bank (2006/2007). "World Bank Mission in Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ eciks (04/05/06). "May finds Kosovo with 50% unemployed".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b U.S. Commercial Service. "Doing Business in Kosovo".

- ^ Economic Reconstruction and Development in South East Europe. "External Trade and Customs" (PDF).

- ^ B92 (02/10/06). "Croatia, Kosovo sign Interim Free Trade Agreement". mrt.com.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ EU in Kosovo (17/02/06). "UNMIK and Bosnia and Herzegovina Initial Free Trade Agreement" (PDF). UNMIK.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The World Bank (April 2006). "Kosovo Monthly Economic Briefing: Preparing for next winter" (PDF).

- ^ EU in Kosovo. "Invest in Kosovo".

- ^ BBC News (03/05/05). "Brussels offers first Kosovo loan".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ UNMIK. "Kosovo in figures 2005" (PDF). Ministry of Public Services.

- ^ BBC News (23/12/05). "Muslims in Europe: Country guide".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ BBC News (20/11/07). "Regions and territories: Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ International Crisis Group (31/01/01). "Religion in Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2007 (U.S. Department of States) - Serbia (includes Kosovo)

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2006 (U.S. Department of States) - Serbia and Montenegro (includes Kosovo)

- ^ Albanian Population Growth

- ^ Demographic explosion in Kosovo

- ^ Kosovo-Hotels, Prishtina - Kosova-Hotels, Prishtinë

Further reading

Malcolm, Noel (1999). Kosovo: A Short History. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060977752.

See also

- Assembly of Kosovo

- Government of Kosovo

- Prime Minister of Kosovo

- President of Kosovo

- Serbs in Kosovo

- Albanians in Kosovo

- Post and Telecom of Kosovo

- National awakening and the birth of Albania

- Demographic history of Kosovo

- Unrest in Kosovo during March 2004

- Metohija

- North Kosovo

- Flag of Kosovo

- 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence